Rewarding Failure – should we?

There are many instances where we all face the uncertainty and the disruption of failure. In our personal histories it might be at exams or driving tests, or on a date, or in front of friends – all leaving us with the embarrassment and frustration at both not attaining our desires while also making fools of ourselves.

In our business lives however, we are told that we ought to fail – regularly and often – in order to learn and take ourselves forward. And yet, the reward systems in place do not encourage this at all. Nowhere that I have heard of are you granted more salary for completing a project that did not work, or given a promotion for submitting an annual report that summarised the year’s results as ‘less good than last year because I tried something that did not work as well”.

So, the question is: “If failure is something we should be doing, why do we not have the reward systems to encourage it?”

Most people would say there is a clear difference between an entrepreneur failing and an employee failing in their role. The main differential is that the entrepreneur has failed with their own time and resources, while the employee is failing using the business’s resources.

But hold on a second! If the purpose of failure is to gain learning and experience, surely this happens in both instances? (Let us assume for the moment that we are talking in both cases about people who do learn from such events – not those that go on failing at the same thing time and again but do not change in the hope that doing more of the same will lead to success).

So long as the employee is not moonlighting or carrying on in cowboy-like disregard for company resources, but is doing so with the agreement and support of their managers, then even failure should be valuable (so long as it was not too costly a lesson – and that is up to the management to balance the costs before the go-ahead is given).

The problem is that managers are tasked with bringing in their activities within (or lower than) budget – which would be counter-intuitive when considering encouraging them to support failure-prone projects. In their eyes, it would be better to choose projects similar to those that they know work well already so that the risk of failure is reduced, and the possibility of success is raised. But this says nothing about the potential for gain – in profits, knowledge, experience and growth.

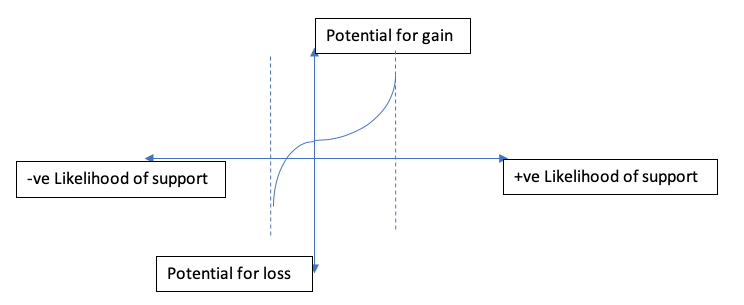

Thus, as the possibility of gain (financial, experience, knowledge) increases, the chances of the manager supporting the project increase. This is a curve rather than a straight line because the lower level of gain are deemed “interesting but not worth the effort” while after a while the potential for gain means that the support rises quickly, until there will be a certain level for gain that garners full support whereupon the curve becomes asymptotic (heads to infinity). The same is true in reverse for the likelihood of support in the event of a potential for loss – although the chances are the support possibilities drop off faster still.

This diagram works for all “gains” but if you split out financial gains from the others, then the diagram changes:

So, once the “Gains” are split out, the lines now show that Experience (which happens whether or not one learns from it – hence is the most certain result) is not much of a driver to encourage managerial support of such projects.

By the time Knowledge is gained from the project (which it should happen whether the project fails or not), there is an increase in likelihood of support from the Manager – but not so much.

Only once there is positive Financial benefit does managerial support start to dramatically increase.

Interestingly, even a ‘failed’ project generates increase in experience and knowledge (albeit not such useful ones). But the drop off is very quick meaning that managerial support will not consider such knowledge or experience gain as justified.

But how does the manager know that such knowledge gain is unjustified – especially in advance of the project being carried out? It seems they are making suppositions about what will be learned…which we infer to mean that they believe they know the results already. But how?

Ultimately, without an external stimulus to encourage knowledge development, management levels will seem likely to revert to what they already know – which in turn takes us back to the existing models rather than try something new.

So, from the point of view of developing new approaches and techniques, what rule of thumb can be identified to encourage managers to push for such projects?

Any ideas and alternatives welcome – please let us know! Contact Carl Kruger at Qualitation